Case Study of Good T&L Practices > List of Case Studies > Professor TSUI Lik Hang

Biography

TSUI Lik Hang is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Chinese and History at the City University of Hong Kong (CityU). He received in his College’s New Researcher Award in 2019-2020 and a Teaching Award (Early Career Faculty Members) from Hong Kong’s University Grants Committee (UGC) in 2023, in recognition of his research and teaching.

He received his bachelor’s degree in history from Peking University and a doctoral degree in Chinese history from the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. Before joining CityU in 2019, he worked as Departmental Lecturer in Classical Chinese at the University of Oxford and Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard University with the China Biographical Database (CBDB). He has held visiting positions and fellowships at Academia Sinica, Peking University, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, and University of Western Australia. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. He specialises in Middle Period Chinese history and culture and the digital humanities. He has published more than 20 scholarly articles and book chapters and more than 60 articles in popular journals and newspapers.

My journey to teaching Chinese history was quite unconventional. In the early 2000s, when most high school graduates were opting to study business, IT, and other “hot” undergraduate programmes, I made the unconventional decision to study history, a “neglected” subject for most people, at Peking University (PKU). I was lucky to have open-minded parents who supported my decision. PKU’s passionate teachers and massive historical resources enabled me to build a strong disciplinary foundation and instilled in me the importance of passing on knowledge to the next generation. PKU’s international environment inspired me to continue my studies at the University of Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship and to conduct research at Harvard University. This international experience allowed me to share knowledge and gain non-native perspectives and digital technologies. My multiple roles and intercultural experience gave me the confidence to become a teacher, adopting “A Digital Deep Dive into Where the Past and Present Meet” as my teaching motto.

I became a history teacher because I believe that Chinese history is an important component in developing civically oriented individuals for our city. To arouse students’ interest in the discipline, I show them why this “seemingly useless” (less practical) discipline is very important and functional (i.e., why study history). I do my best to bring heritage to life by teaching Chinese history and helping students develop an objective, fair, and critical approach to the study of history. By training their critical thinking and information literacy, which are transferrable skills, I help them understand history from a broader and more reflective perspective. By embedding digital elements, I make learning more effective and enjoyable (i.e., how to study history) for this generation of digital natives living with machines.

“Review the Old to Know the New”

This great Confucius saying articulates my teaching philosophy. As a historian, I believe that studying historical events and their underlying causes can identify patterns and connections to better understand and approach the contemporary world. Whenever new information emerges or social and cultural values evolve, historians redefine the narratives of history to help explain contemporary issues. With this belief, I inspire students to adopt both digital and non-digital means to study, discuss, and analyse history, develop analytical and problem-solving skills, and possibly apply their findings to think about contemporary issues.

To nurture students’ ability to connect history to their own world and thereby define the future, I have carefully (re-)designed my courses to develop students’ skills in assessing evidence, conflicting interpretations, and past examples of change, and to foster their ability to grasp and realise “second-order concepts” (derived from elements that examine history in more depth than just recounted facts). One example is the redesign of a course focused on exploring the history of cultural globalisation. I guide students to draw insights from historical perspectives, encouraging them to develop a more grounded understanding of the complexities of globalisation and to critically examine our assumed cultural traditions as well as the histories of everyday objects that are so close to our lives. Through this process, students become more perceptive in their assessment of information and opinions concerning contemporary global cultures.

Dialogic Path to the Study of History

Both the Greek philosopher Socrates and the Chinese thinker Confucius encouraged a shared dialogue between teachers and students, sparked by the teacher’s incessant questioning, in a concerted effort to explore the underlying beliefs that shape students’ views and opinions. Inspired by Socrates, the Oxford tutorial system offered me the opportunity to participate in conversations with my tutor and classmates in small groups or even one-on-one tutoring when I was a PhD student. Such interactions taught me to develop independent thinking with confidence and self-reliance.

Now a teacher, I use such practice and engage students in their study by encouraging them to learn actively, think critically and independently, and join academic discussions with the teacher and peers, ask meaningful questions, and reflect on or give critical answers to questions (Figure 1). This is particularly important because the academic study of Chinese history is unfamiliar to most students who often have only a commonsensical understanding of it. Interactivity, active learning, cultural understanding, and multilingual capabilities are thus integral to how I generate knowledge with my students.

The Socratic Method Transposed to the Digital World

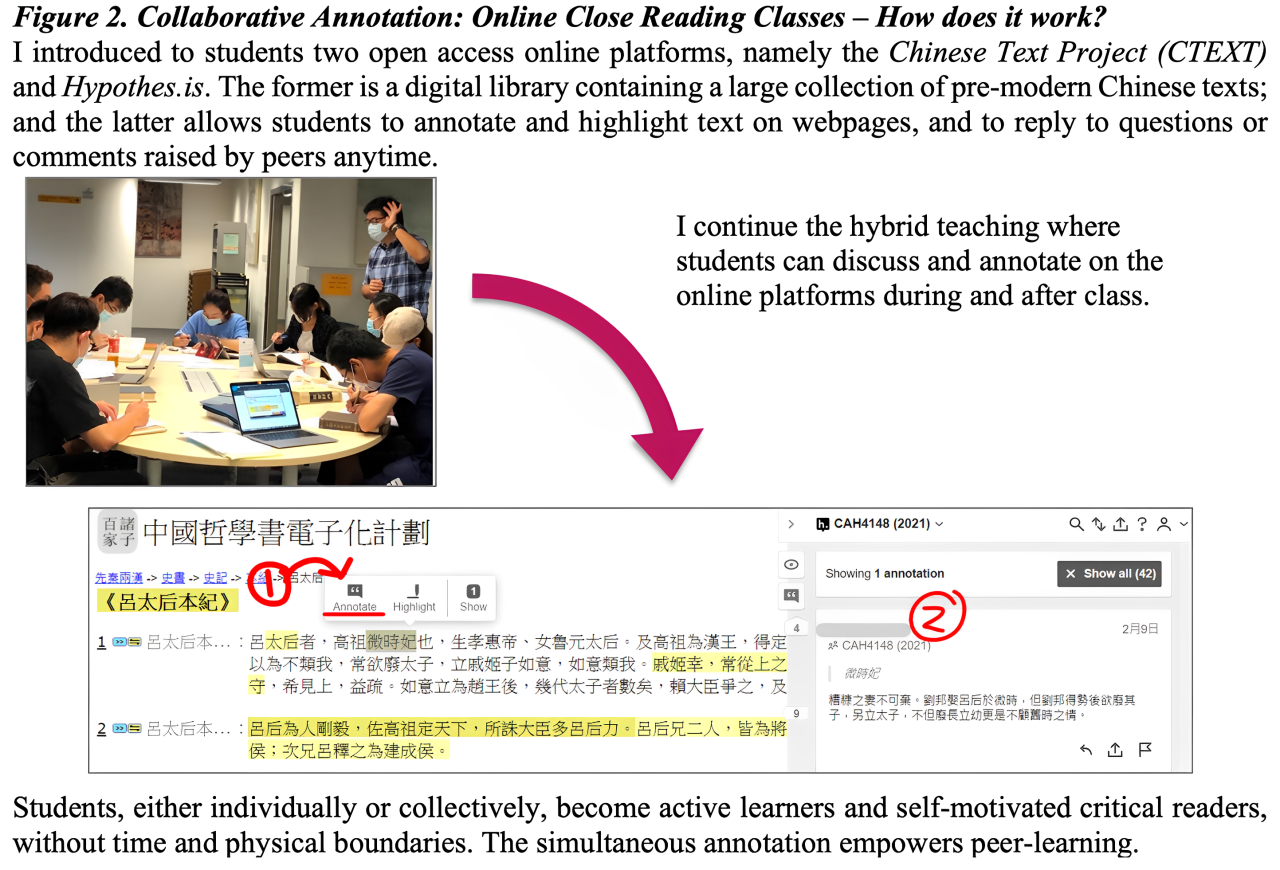

The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected our teaching in 2020, shifting it to an online environment for a significant period of time. Nevertheless, I attempted to cope with this challenge by developing collaborative annotation exercises by pairing digital tools with online text repositories, based on my expertise in the digital humanities. The tools recreated and expanded the lively environment of reading seminars online, much different from the stale online bulletin boards. This innovation proved to be effective in enthusing and engaging students in a fully online environment, particularly in creating momentum for reading and discussing textual sources. This transformative learning process gave students the confidence to formulate their own views and interpretations. This confidence is essential for grasping the “second-order concepts” in the study of history, to examine history in deeper, more holistic contexts than factual information alone. The online environment also encouraged shy students to show initiative and deep thinking in front of the whole class.

Good remote teaching should not just be about moving teaching online but also about leveraging the online environment to generate synergies. Echoing CityU’s discovery-driven curriculum, my approach effectively increased collaborations among students with the boost of digital tools. Even today, I continue to use a similar approach, providing students with online guides and resources outside of class. Class time is primarily spent on active learning activities such as discussing and responding to my questions and short lectures (Figure 2).

Digital Humanities: A Learner-centred Approach to Studying History with New Tools

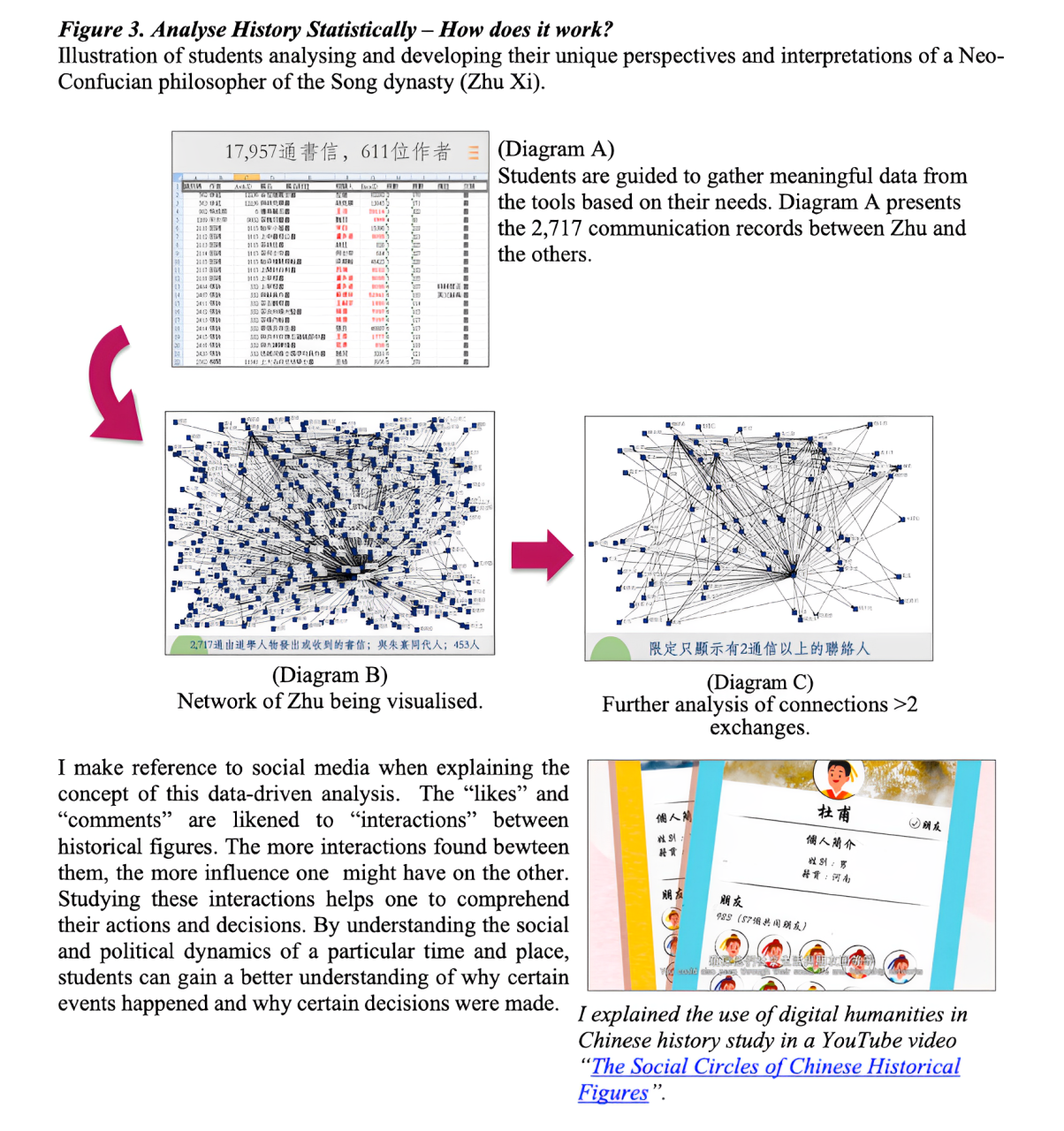

The digital humanities combines traditional humanities research with digital technologies (e.g., data analysis, text mining, and visualisation). It is a way to ask, redefine, and answer questions with a more intelligent set of tools that are deeply rooted in our everyday lives. My expertise allows me to bridge the gap and demonstrate that the application of digital technologies to the study of history not only improves efficiency but also provides many interesting new perspectives for research (e.g., relationships between historical figures) (Figure 3). Historical research is no longer “old-fashioned”, and the study of history can also incorporate elements that keep up with the times, making this subject innovative and enjoyable. The learner-centred approach I adopted for my university’s Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts in Chinese and History programme and general education courses are good examples of the effectiveness of exposing students to digital tools. I create opportunities and provide students with the resources needed to adopt a more active learning strategy.

With the data available through the large-scale datafication/digitisation projects of Chinese history since the 2010s, in which I have been involved, undergraduate students find it more convenient to access original historical sources in digital form. “Googling” is already practised by all students, but they need dedicated guidance to look for digital information thoughtfully and carefully. For instance, the CTEXT website provides students with key digital texts of canonical works of Chinese history, and the CBCB I contributed to helps students find biographical and relational information about historical individuals. With my targeted guidance on how to evaluate the quality of digital sources, students can build historical knowledge through a new pathway. The strategy is part of technology-driven teaching that is revolutionising student learning.

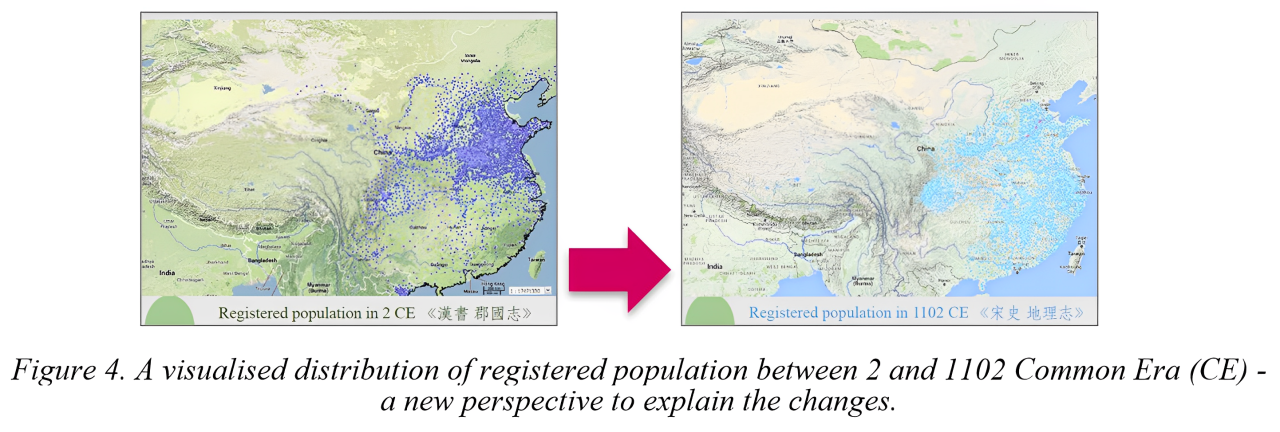

The power of data lies not only in their collection but also in their interpretation, analysis, and usage. I guide students to integrate existing online datasets with hand-picked innovative digital tools to map locations, draw timelines, annotate historical texts, and look up digital biographies from imperial China (Figure 4). I also create learning materials to strengthen students’ information literacy through digital tools. These tools help to instil an element of “discovery” and implement a learner-centred approach to learning history. This data-driven approach to learning enables students to participate more fully and proactively as budding “researchers” when tackling academic questions, such as when they attempt to decipher and contextualise a historical text in Classical Chinese.

Human + Machine Complementarity: Socratic Questioning + Artificial Intelligence Tools

Society is currently discussing generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) and some are concerned about the challenges it could pose to the education system. For me, GenAI tools complement and augment the Socratic way of teaching. While Socrates encouraged continuous questions and answers between students and teachers, I consider GenAI tools inevitable for teachers and a potential peer for students in their learning. We should take advantage of the functionality it provides, but like their human peers, students must be trained to challenge any GenAI tool with constructive, ongoing probing questions. The students’ horizons will in turn be broadened. They also face the challenge of checking and reacting to what their AI peer “says”, which is a precious learning opportunity. I believe Socrates or Confucius would appreciate such a knowledgeable peer with whom to construct a meaningful discussion!

Combining the Old and the New: Appreciating the Traditional Ways of Feeling History

Although I use digital technology to teach a seemingly “traditional” subject, I encourage students to also appreciate conventional learning methods (Figure 5). I occasionally teach my classes in the library to teach students how to browse and search (the old-fashioned way) for the most useful reading materials. The classification and sequencing of books in the library, for example, shows how knowledge ought to be organised and arranged. I bring students to local museums and organise virtual tours of overseas museums. Visiting museums to see the artefacts allows students to observe for themselves and immerse themselves in past environments. I also guide them to produce podcast programmes about history, giving them a chance to re-enact history with their own voices.

After all, understanding how cultures, periods, and contexts are very different from our own is the goal of humanities education. Equipped by digital tools, we should be able to make this learning even more rewarding and enjoyable (Figure 6).

Generalisability of Teaching Initiatives

I also actively find ways to apply my teaching initiatives to other disciplines and teaching settings. For instance, students in non-humanities subjects also find my approach useful:

“As a student with no humanities background, I see Prof. Tsui’s important role in my academic advancement as my MPhil supervisor. As an undergraduate computer science major, I received a lot of help from Prof. Tsui on how to apply my programming knowledge to the humanities. He shared with me links to cutting-edge digital humanities workshops around the world and invited me to help in the digital humanities conferences he hosted. These activities gave me a better understanding of how the Text Encoding Initiative, big data, and GIS can be used to help humanities scholars. During my MPhil studies, I produced two maps of Song dynasty councillors through the GIS system, which would have been impossible without communicating with him about producing GIS maps and how they could be used in academic research.”

(An MPhil graduate advisee in Chinese and History)

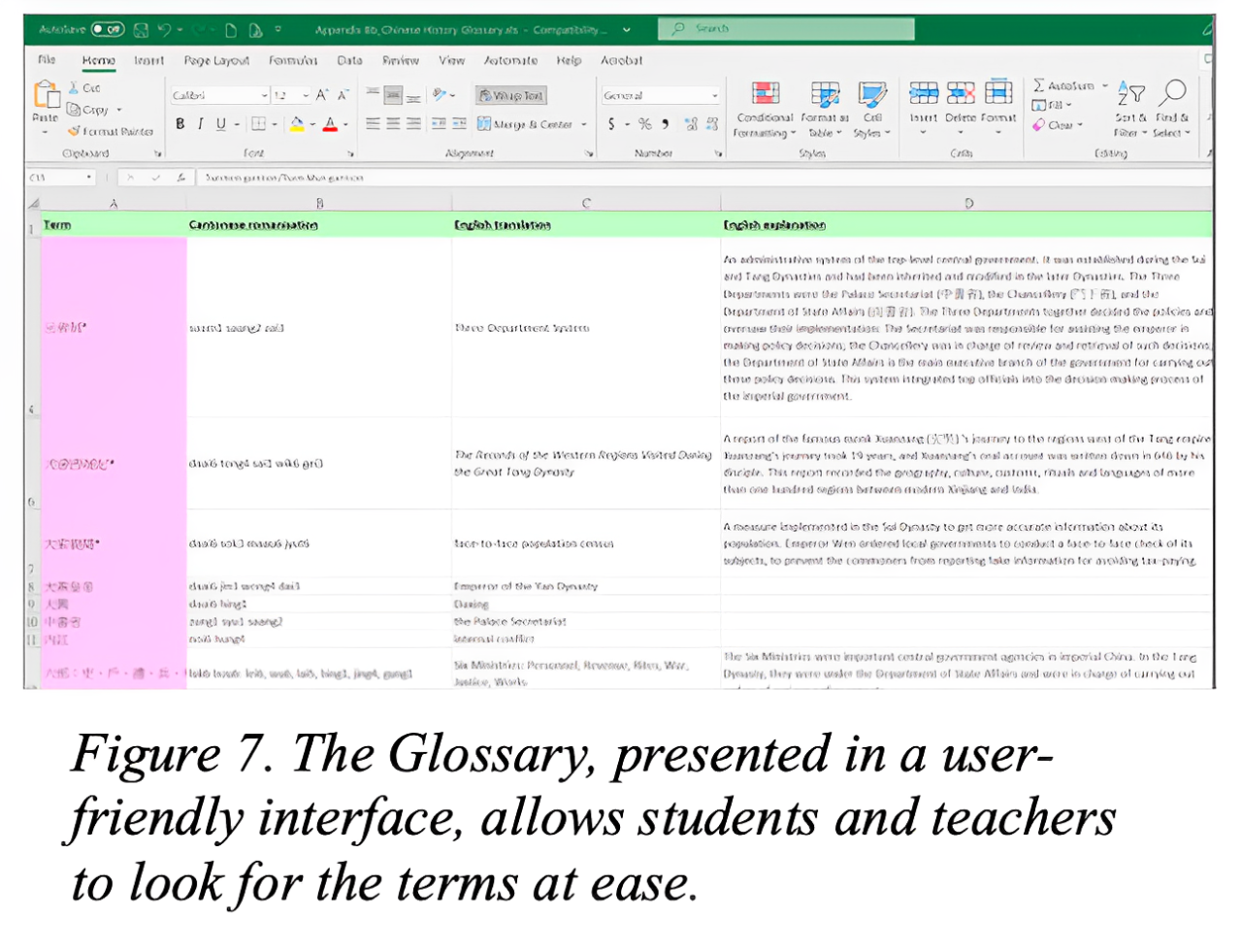

Impact on Students Beyond CityU

Given the growing importance of history education in Hong Kong, I have led initiatives to transfer knowledge of Chinese history beyond the higher education sector. Since the 2018/19 academic year, Chinese history has become an independent compulsory subject at the junior secondary level in the city. This posed some learning difficulties for non-Chinese students from local kindergartens, primary, and secondary schools given their limited written Chinese proficiency. I therefore led a team of colleagues to create a glossary for the Education Bureau (EDB), to help non-Chinese secondary school students to learn and their teachers to teach Chinese history terms. The glossary, available free of charge on the EDB website, provides English translations and explanations of 2,433 terms commonly used in Chinese history teaching (Figure 7). With the glossary, students can not only understand the terms but also learn Chinese culture, adapt to the local education system, and foster a better cultural understanding of their hometown in the Chinese context. This effort received a Knowledge Transfer Award from CityU’s College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences.

Spearheading Transdisciplinary Digital Learning and Research

To amplify the potential of the digital humanities, I became the founding convenor of the “Digital Society” research cluster in my College at CityU, a role I held until 2024. This role allowed me to mobilise and encourage collaborations between colleagues in different fields, such as English, media and communications, and public and international affairs, to address pressing issues in our increasingly digital society. I am also my college’s representative for Digital Learning, overseeing course design and administration to incorporate educational technology into teaching, as well as encourage blended learning efforts among colleagues.

Knowledge Transfer and Service

I value the importance of knowledge transfer, collaboration, and community-building. In this capacity, I have organised/co-organised a dozen conferences to disseminate academic know-how in the digital humanities, and I have been invited to deliver talks and workshops locally and internationally (Figure 8). Highlights include speeches at MIT and other universities, as well as talks for local schoolteachers. These efforts have encouraged humanities students to improve their digital literacy and enabled other majors to begin their training in the humanities and Chinese history.

Recognising the need to build the capacity of teachers and learners through online and public engagement, I co-founded the WeChat public account 01Lab to distribute learning resources and tutorial materials to readers. It has over 10,000 followers and received international recognition with the 2019 DH (Digital Humanities) Awards.

I have promoted the study of Chinese history and digital humanities across various media such as TV, print, and on the internet (Figure 9). My contributions to the popular TV documentary “The Story of China” by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) & Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) are widely broadcast internationally and clips are often used in classroom teaching.